I had just given a talk to an MFA class when a young woman stood up and asked: How can I make writing fun again? There was a desperate tone in her voice, and I could tell she was struggling with the possibility that maybe the writing life was not for her. Not because she didn’t want it, but because it didn’t seem to want her, the lack of fun being the clearest sign of this rejection.

My first impulse was to answer with a question of my own: “Who said writing is supposed to be fun?” I had just finished a novel about a young girl recovering from depression that had taken me four years and three complete re-writes to finish and I was tempted to describe in lurid detail the mental, physical and emotional hardships endured. Restraint and compassion prevailed, however, and I focused on the last word of her question: How can I make writing fun again? Writing had once been fun for this young woman, so I asked her to go back in time and remember the early excitement of creating.

We start off our writing life with a mysterious, delightful, irrepressible urge that is very similar in its freedom and spontaneity to the play of a child. This “beginner’s mind” knows no rules, moves wherever the winds of expression take it and contains a self-forgetfulness that is the very essence of fun. What happens to this childish sense of fun as we progress in our writing journey? Why does it diminish and sometimes disappear? Gradually, the unrestricted and inviting space of play begins to be crowded with all kinds of expectations: I would like my writing to be rewarded, to be admired by many, to sparkle with award-winning expertise. I cease to be a child following the whims of my imagination and become an anxious worker burdened with the heavy load of ambition and the fear of not measuring up.

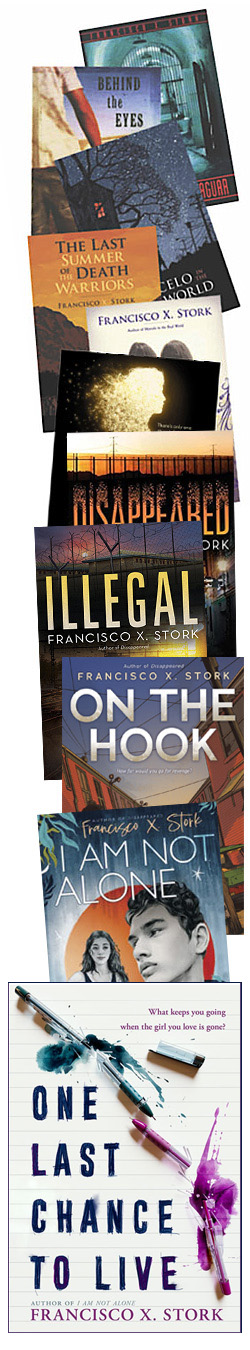

The young MFA student’s question was present in my mind as I wrote On the Hook, my young adult novel published this past May. On the Hook is the story of Hector, a smart young man whose main goal is to graduate, go to college and become an engineer so that he can get his family out of the public housing projects of El Paso. Unfortunately, Hector is noticed by Joey, the brother of the local drug dealer, and after a series of violent events Hector and Joey end up in a reformatory school in San Antonio. There they must each find a way to “unhook” themselves from the violence, hatred and desire for revenge that consumes them and maybe even learn the true meaning of courage.

On the Hook is a re-creation of a book I originally wrote in 2007. I had tried unsuccessfully to revise the old story many times since the book was first written. Each revision felt more and more burdensome and the result more frustrating. Then in 2018 I decided to start again from scratch. Instead of revising the old, I tried inventing something new. Some of the characters kept their old names, but they became different people – more real, more complex, more dynamic. The obstacles that they must overcome to survive and to grow were harder, more intricate. I threw out the illusion of revising a story to some ideal of perfection and gave myself over to the humble task of creating something new, something honest and true.

But the writing was not just for me. As I wrote, I kept in mind the image of a young man like Hector. A young man with a good heart that had taken a turn toward hatred and violence. As I wrote, I asked myself, how can I get this young man to see himself in the characters of the story? What can I give this young man so he can re-discover the goodness in his heart?

There’s a scene in On the Hook where Hector wins a prize for an essay he wrote about the phrase “the pursuit of happiness” from the Declaration of Independence. In the essay Hector describes how his father worked as a migrant farm worker when he first came from Mexico and then in a pants factory for many years until, after two years of night school, he finally landed his dream job as an auto mechanic. For Hector’s father, working at a job he loved and the obligation to support his family were part of the same pursuit of happiness. Similarly, for me, the fun of creating goes hand in hand with the responsibility I feel toward young readers.

I am grateful that I was able to transform an old story into a new creation that was fun to write even while fulfilling the desire to create a work that was truthful and meaningful. Sometimes I am tempted to substitute the word “joy” for “fun” because it is easier to imagine the possibility of joy even in the midst of days and months of discipline and hard work. But the older I get, the more I like the word “fun” when it comes to writing. Creating is fun. It is both fun and difficult, an obligation and a choice, a gift and a giving. All of those things rolled into one.

{ Comments on this entry are closed }