I had just given a talk to an MFA class when a young woman stood up and asked: How can I make writing fun again? There was a desperate tone in her voice, and I could tell she was struggling with the possibility that maybe the writing life was not for her. Not because she didn’t want it, but because it didn’t seem to want her, the lack of fun being the clearest sign of this rejection.

My first impulse was to answer with a question of my own: “Who said writing is supposed to be fun?” I had just finished a novel about a young girl recovering from depression that had taken me four years and three complete re-writes to finish and I was tempted to describe in lurid detail the mental, physical and emotional hardships endured. Restraint and compassion prevailed, however, and I focused on the last word of her question: How can I make writing fun again? Writing had once been fun for this young woman, so I asked her to go back in time and remember the early excitement of creating.

We start off our writing life with a mysterious, delightful, irrepressible urge that is very similar in its freedom and spontaneity to the play of a child. This “beginner’s mind” knows no rules, moves wherever the winds of expression take it and contains a self-forgetfulness that is the very essence of fun. What happens to this childish sense of fun as we progress in our writing journey? Why does it diminish and sometimes disappear? Gradually, the unrestricted and inviting space of play begins to be crowded with all kinds of expectations: I would like my writing to be rewarded, to be admired by many, to sparkle with award-winning expertise. I cease to be a child following the whims of my imagination and become an anxious worker burdened with the heavy load of ambition and the fear of not measuring up.

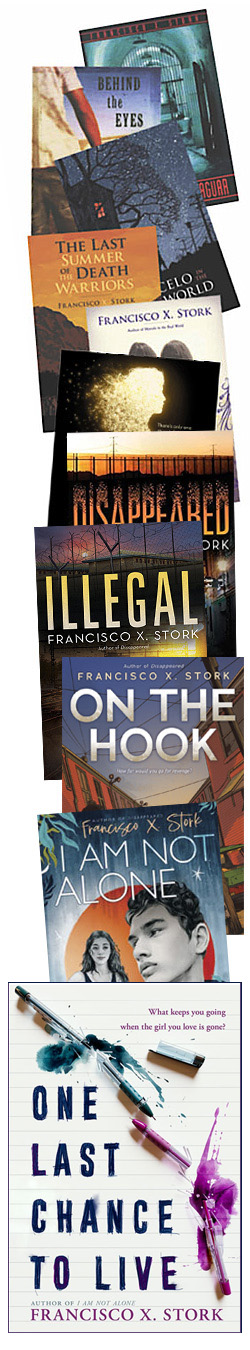

The young MFA student’s question was present in my mind as I wrote On the Hook, my young adult novel published this past May. On the Hook is the story of Hector, a smart young man whose main goal is to graduate, go to college and become an engineer so that he can get his family out of the public housing projects of El Paso. Unfortunately, Hector is noticed by Joey, the brother of the local drug dealer, and after a series of violent events Hector and Joey end up in a reformatory school in San Antonio. There they must each find a way to “unhook” themselves from the violence, hatred and desire for revenge that consumes them and maybe even learn the true meaning of courage.

On the Hook is a re-creation of a book I originally wrote in 2007. I had tried unsuccessfully to revise the old story many times since the book was first written. Each revision felt more and more burdensome and the result more frustrating. Then in 2018 I decided to start again from scratch. Instead of revising the old, I tried inventing something new. Some of the characters kept their old names, but they became different people – more real, more complex, more dynamic. The obstacles that they must overcome to survive and to grow were harder, more intricate. I threw out the illusion of revising a story to some ideal of perfection and gave myself over to the humble task of creating something new, something honest and true.

But the writing was not just for me. As I wrote, I kept in mind the image of a young man like Hector. A young man with a good heart that had taken a turn toward hatred and violence. As I wrote, I asked myself, how can I get this young man to see himself in the characters of the story? What can I give this young man so he can re-discover the goodness in his heart?

There’s a scene in On the Hook where Hector wins a prize for an essay he wrote about the phrase “the pursuit of happiness” from the Declaration of Independence. In the essay Hector describes how his father worked as a migrant farm worker when he first came from Mexico and then in a pants factory for many years until, after two years of night school, he finally landed his dream job as an auto mechanic. For Hector’s father, working at a job he loved and the obligation to support his family were part of the same pursuit of happiness. Similarly, for me, the fun of creating goes hand in hand with the responsibility I feel toward young readers.

I am grateful that I was able to transform an old story into a new creation that was fun to write even while fulfilling the desire to create a work that was truthful and meaningful. Sometimes I am tempted to substitute the word “joy” for “fun” because it is easier to imagine the possibility of joy even in the midst of days and months of discipline and hard work. But the older I get, the more I like the word “fun” when it comes to writing. Creating is fun. It is both fun and difficult, an obligation and a choice, a gift and a giving. All of those things rolled into one.

September 1, 2021

For the Fun of It

December 6, 2019

Letting Go

On this late autumn day, the elms and oaks around my house seem determined to let go of all the leaves that have died on their limbs. Everywhere I look there is a letting go. The sky has let go of blue and allowed itself to be covered with a thick mantle of gray.

I am reminded of the letting go that I need to do. I am sixty-six (not that old as actuarial tables go) but like you and everyone and everything else that has been born, I am on my way to that final, total, letting go and I believe that it is time to shed what is no longer needed in this final stage of the journey.

It’s not a long list, the things I need to detach from. They are internal things mostly, like the ambition for worldly recognition that served me so well when I was young and I yearned to be somebody. Now ambition and the search for glory and rewards are a heavy burden and I would like, if at all possible, to travel light.

Whenever I try to explain to people that in this phase of my life, I wish to let go of no-longer-needed wants, they get worried that I may be in the grips of depression. Sometimes, I see disappointment in their eyes. I am bailing out on the American dream to strive, always to strive for more, to never quit. I am giving up on living life to the fullest. Why, there are people older than me running marathons, running billion-dollar enterprises, running for president of the United States. A few of my more literary friends have even taken to quoting the famous lines from Thomas Dylan’s poem:

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

I try to explain that, actually, raving and raging are at the top of the list of what needs to go. And if there is any burning inside of me, it will be more like the gentle flame of a candle that stays lit in the windstorm. But isn’t rage needed now more than ever? Isn’t giving up on rage the equivalent of not caring, of standing silent in the face of suffering and injustice? Am I being irresponsible? I respond that anger is not the strongest force, the fiercest weapon, but my words are taken as defeat.

I want to keep on working, fighting if you will, by being as useful to others as I can. What I am letting go of is the old motivation and the old methods of work. I let go of working for the fruits of my labor and focus on the sincerity of the effort. If I work with honesty and truth the outcome will not matter. I embrace work as a gift. The energy and ability to work, the talent, the creativity behind it, all is a gift and my only hope is to pass the gift successfully to others. The method too will change from hurried and anxious productivity to work done with the urgency and seriousness of an inner calling, a sacred obligation. Waiting with receptive attention, listening, silence, the fecundity of leisure — all these will be part of the work. The value and priority of different daily tasks will change. What if everything I do each day is equally important? What if playing with my grandchildren is as significant as writing a story? What if I write a story with the same love with which I hold my grandchild? And what if love becomes the burning purpose of my work?

So many world traditions recognize old age as a special time. A spiritual time when a person can let go of the business of making a living and spend time looking care-fully at creation or searching for the presence of a creator, or developing virtues like humility, patience, kindness. Here in America that kind of letting go seems like giving up or, worse, cowardice. But letting go is an act of courage. It is choosing to finally, finally, follow the beat of your own drum. It means, if it comes to that, living on the margins of what is approvable by the world you live in. Courage could mean a solitude that is entered bravely, but not without fear. I am letting go of the images of myself that have served me well since I was a child. Who am I if not the talented boy who could read hardcover books in first grade? Or the dutiful lawyer or the Latino writer? Who am I, really, without these comfortable images?

These old, old, tress let go of their leaves effortlessly. For them, the process of letting go each year is part of their becoming and their becoming happens just as it is meant to happen. It is, unfortunately more complicated for me. The acorn “knows” it will become an oak tree. My own becoming takes some figuring out. Not just who I am but who I am supposed to be. Who is the person I am finally to become? For I feel the presence of becoming in my old heart and it is not the same restless energy of forty years ago. To find out where this becoming is taking me, I must let go of all that is not true, of all that belongs to others, of all those cherished fantasies. No one said it wasn’t going to hurt.

And yet, this letting go is not without a quiet joy, like the joy of the trees swaying in the wind, or the joy of the spiraling, falling leaf. I don’t know how to describe this joy. It is a paradox. It is joy filled with a light that is both dying and living.

I let go of trying to understand it.

January 1, 2018

Faith and Courage

These past few months I have been working on faith and courage. For faith and courage are both gifts of grace and qualities of being that we construct. Like one day going outside to your backyard and finding the wood, the hammer, nails, the saw. Where did they come from? Who put them there? Regardless of the answer to these questions, the message from the materials is irrefutable: Build. Some time is needed, before commencing a new work, to build the faith and courage that will carry me through. I am going to start on a novel that follows Emiliano and Sara from where I left them in Disappeared. The preparation for this new work has been internal – building inside of me the faith and courage for the task. Gradually I construct the vessel of faith and courage. I ask the two questions that Annie Dillard says are asked by the book to be written: Can this book be done and can I do it? The first question needs to bring risk otherwise I have not yet found the book that I must write. If the answer to “can it be done” is an easy yes then I am not there yet – not yet reached the depths of truth where lies the book that only I can write. If it’s an easy yes, I am still too much on the surface of what the world wants and not yet reached the risky depths of that place of what the world needs and only I can give. So in a way courage comes first and it also comes last. Or better yet, faith and courage are only two separate realities here where words are needed but in my heart they are one. It takes courage to find the book that calls for my all and it takes faith to know that this is what I must do. And then it takes courage/faith to do it, to keep at it patiently through the days and months that lie ahead. Faith is not so much a confidence, although there is that. Faith is more like an inevitability and a certainty that despite the risks of failure nothing else but what I set out to do will do. It is not so much a reliance on my abilities as the certainty that what is needed will come at the right time. Why? Because I am answering a deep call that asks for much and my response and my faithfulness to what is being asked is all that is needed for life and light to do their part. But how do you build faith and courage, the elements needed for the work? What is my part with the boards and nails and tools? A lot of the building consists of waiting. A kind of waiting with a certain alertness – as if you were spending the night in the desert where you knew rattlesnakes liked to crawl. I wait and with wary attention watch the doubts that slither through my mind. Will the book be liked? I watch various plot lines and characters and search for the uniqueness that can only come from me, from what I have lived, from the truths that have revealed themselves to me through pain and joy. I know I reach some truth worth holding on to when I hear a small rattle of fear. That’s the signal that must be followed. Now, faith/courage comes like a seed and then a tender shoot that must be protected. I don’t know how to offer this fragile life protection without creating some kind of barrier. If I could carry faith/courage into the market place without concern that it would be destroyed or harmed, I would. Maybe some day. But now, all I have is hands to keep the noisy winds away. Solitude and isolation in some healthy measure is the best that I can do. I must be in the world but not of the world, as best as is humanly possible for me. A good monk goes into the seclusion of the monastery not to hide but to find. So I protect faith/courage for the sake of giving. I say no for a while, a gentle, gracious no, because I am responding with all the faith and courage I can muster to a yes. Faith/courage begins in love and ends in love.