Donna Freitas, a teacher in the Religion Department at Boston University and a writer of young adult novels (The Possibilities of Sainthood – Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2008), invited Cheryl Klein (my editor at Arthur A. Levine Books/Scholastic) and me to talk to her Religion and Children’s Literature class tomorrow. I thought I would jot down some thoughts here in preparation for some of the tough questions I may get asked. In particular, I’m worried about someone asking me: “What role does religion play in Marcelo in the Real World?” So here’s a practice run of what I might say. Marcelo, the protagonist of Marcelo in the Real World, is a young man consumed with God and all things religious. God and the Holy Books that pertain to God are his “special interest.” Marcelo prefers the term “special interest” to the term “obsession” because obsession has certain pathological connotations. When you are obsessed with a subject you are forced by an inner force to think about that subject. A special interest, on the other hand beckons your attention without compulsion. Marcelo enjoys thinking about God. He chooses to think about God and read the Holy Books that pertain to God. He would rather do that than anything else. His religious interest is non-denominational. He likes all religions. He reads all kinds of Holy Books. He manifests no sense that one religion is better than another. Moreover, Marcelo’s interest is not simply intellectual, he hears something that for lack of a better word, he calls “music” that no one else can hear. This music fills him with a sense of “longing” and of “belonging.” What happens when someone with Marcelo’s faith, let’s call it, is asked to function in our modern corporate world? I believe that this question, at the heart of the book, is ultimately a religious question. It is not a question that is associated with any religious dogma. It is the question of how a a faith can survive the pressures of the modern, competitive, ego- centered world. What do you do if like Marcelo, you are suddenly overcome with the question: “how do I live with all the suffering?” What if the suffering in the world grabbed you like an iron hand around your throat and wouldn’t let you go? What if you are privileged to see and sense God’s goodness in you, while at the same time, you are forced to witness the pettiness and meanness and evil that surrounds you? How do you go on living? These are the questions, living, burning questions of Marcelo’s life. To Marcelo, these are “religious” questions – and so, I would say, that the role of religion in the book is in the asking certain type of questions when the asking is done with mind, heart, body and soul.

October 20, 2008

May 27, 2008

El Paso, Texas

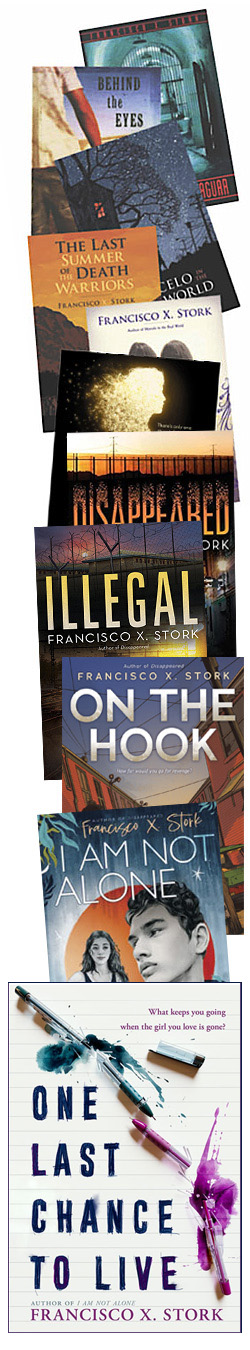

I was invited last week to talk to the 7th and 8th graders of Indian Ridge Middle School in El Paso, Texas. I work hard during the year trying to get invited to at least one El Paso school. First and foremost is the food. Mexican food restaurants on every corner. All of them with a grandmother or two cooking in the back. I grew up in El Paso and the setting for Behind the Eyes (at least the first part of the story) is in El Paso. A large part of my first novel, The Way of the Jaguar also takes place in El Paso. So it makes perfect sense to have someone like me spend a couple of days with El Paso kids. Now I have to tell you right away that these speaking engagements are hard work. At Indian Ridge, met with seven group of kids each day (each group for an hour). There was half an hour off for lunch where, you guessed it, I had tacos. What I try to do during these little talks is talk a little about my life and my books and how the two play off each other, how something actual gets transformed by the imagination into fiction. My favorite part, however, is when I get the kids to write for a few minutes. We pretend that we are writing in a journal that no one will read. I’ll read what they write but I don’t know them so it’s like writing for themselves. The question that elicits the deepest responses is this one: “What is the worst thing that has ever happened to you.” I tell them to write for five minutes without lifting their pencils from the paper, without thinking. Just write. Sometimes, one or two will volunteer to read out loud what they wrote. I bring the hundred of sheets of paper home and I read them. I read about death and divorces. I read about abuse and addiction. I read about rejection and failure. Their writings are a reminder of to me of what a young person of fourteen and fifteen is capable of thinking, feeling, enduring. Their writings are a reminder to me of why I write.